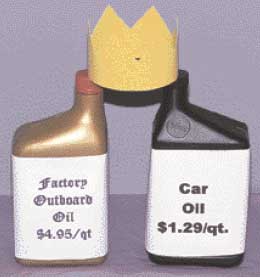

Duke of Oil

Are marine four-stroke oils any better

than less expensive automotive lubes?

We test 'em to find out.

by Bill Grannis

With the proliferation of four-stroke outboards in recent years, boaters have yet another emotional subject to expound on. Joining the never ending debates on which boat is faster, whose engine is more powerful, or what spark plug is best, a new controversy is brewing. This time, instead of family feuds, fisticuffs and the occasional bar brawl about two-stroke lubricants, the four-stroke crowd is embroiled in its own controversial confrontations concerning outboard oils.

Being on the cutting edge of all things outboard, Bass & Walleye Boats tested specialty marine four-stroke oils, and compared their prices and formulations to popular automotive oils. There's a big price difference between the two groups, and we wanted to see what you get for your dough. Various oils were sent for laboratory analysis. We also included a sample of used oil from a Yamaha F225 four-stroke to see what 100 hours of running does to oil (see sidebar). And to gain an idea of each lube's potential corrosion resistance, we placed steel plates soaked in different oils in a saltwater environment.

Surprising Findings

Four-strokes have completely different requirements than two-strokes, and thus require separate lubrication parameters. These outboards are similar to automotive engines in that they have pressurized recirculating oil systems; most also use replaceable oil filters. Additional maintenance is necessary every 100 hours or so. This consists of draining, replacing and disposing of several quarts of engine oil and the filter.

Just as automotive oils are classified by the American Petroleum Institute (API) and Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE), four-stroke marine oils for outboards, inboards and sterndrives will soon be certified under standards set by Chicago-based National Marine Manufacturers Association (NMMA). According to Tom Marhevko, the association's director of engineering standards, certified oils will be labeled FC-W (four-cycle-water-cooled), and will have to pass test sequences that include fuel dilution resistance and corrosion protection, as well as elevated temperature operation and lubricity at high rpm. These should be available late this year after the oils are certified at independent laboratories. Just like the TC-W3 rating defined the industry's standard for two-stroke outboard oils, FC-W oils will set the standard for four-stroke powerplants.

Multitasking

Lubricating moving parts is only one of the many jobs a four-stroke oil has to accomplish. Besides keeping metal components from scraping, it must remove heat from internal engine areas, clean up combustion byproducts, neutralize acids, prevent sludge deposits and protect against corrosion—all while being subjected to high temperatures, moisture and oxidation. It has to do so continuously for as long as a year (or 100 hours of use) without giving up.

To put this in perspective, your car loafs along at 2,500-RPM at 70-MPH, but an outboard cruises at 4,000 to 6,000-RPM (or higher) for hours at a time. This is equivalent to going about 100-MPH in a car. Figuring 100 hours between oil changes, that equates to 10,000 miles. If you drove that fast all the time, how many of you would go that far without changing your vehicle's oil? Then, too, outboards are asked to idle or slow-troll for long periods, and are often operated only occasionally, then stored for long periods. It's a tough life.

Four-stroke engine oils are a complex blend of ingredients. Various concoctions of heavy-grade base oils form the "body," and specialized additives are blended in to perform specific tasks. These additives make up 10 to 20 percent of the oil, and consist of anti-rust, anti-foam and anti-wear agents, detergents, dispersants, viscosity modifiers and other performance enhancers. In many cases, the individual ingredients do more than one job and all must interact to meet the oil's design characteristics.

Our shoot-out compared four-stroke oils from major outboard manufacturers with familiar automotive brands. Most blends were fossil-based, although we also tested synthetics.

Most four-stroke outboards use canister-style oil filters that need to be replaced after 100 hours of use. Smaller engines utilize oil screens that require periodic cleaning.

Lubrication Chemistry

The oil analysis report (see sidebar) shows the differences and similarities of the lubricants we tested. Some products may use a large amount of a certain additive or smaller amounts of various chemicals to achieve the desired effect.

Zinc and phosphorous combine to form zinc dialkyl dithiophosphate (ZDDP), which is not only a very cost-effective anti-wear agent but an antioxidant, as well. The more expensive molybdenum is often used in small amounts as an anti-wear additive in addition to ZDDP, and also has some antioxidant properties.

Detergents and dispersants keep the engine clean and protect it from sludge by keeping contaminants mixed with the oil so they don't settle out. Have you ever looked into a washing machine when the water appeared dingy and gray and wondered how the garments could come out clean? It was detergents that removed dirt from the clothes and dispersants that kept the soil in suspension, preventing them from redepositing on the clothing. Magnesium and calcium do the same thing for motor oils, as well as neutralizing combustion acids.

Boron is a popular anti-corrosion element. Silicone is an anti-foam additive that also provides corrosion protection. An additive package may have completely different characteristics than each of its individual components.

Laboratory Analysis

For lab testing, we chose each of the outboard manufacturer's four-stroke oil offerings, as well as five popular automotive oils to see if there were significant differences. Initially, we were going to limit the assortment to fossil oils, but with recent interest in synthetics, we added Mobil 1 synthetic to our automotive selection due to its widespread availability. There are many fine oils on the market, but budget and time constraints limited our choices.

Our spectrometer chart lists the oils, prices per quart and the parts-per-million (PPM) of the common elements that were detected. For those of us challenged by math, 1000-PPM equals 0.1 percent. Note that no two oils have exactly the same formulation, putting to rest the urban myth that petroleum company "A" just relabels its oils and sells them to company "B."

SPECTROMETER ANALYSIS OF OUTBOARD AND AUTOMOTIVE OILS

Results are in parts-per-million.

| Brand | Cost per Quart US $ |

API Rating |

Silicone (Anti-foam) |

Boron (Anti-corrosion) |

Magnesium (Dispersant/ Detergent) |

Calcium (Dispersant/ Detergent) |

Phosphorus (Anti-wear/ Antioxidant) |

Zinc (Anti-wear/ Antioxidant) |

Molybdenum (Anti-wear) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yamaha 4M 10W-30 |

4.50 | SJ | 12 | 278 | 843 | 288 | 1053 | 1154 | 1 |

| Sierra 10W-30 |

3.95 | SJ | 5 | 258 | 719 | 325 | 1260 | 1372 | 0 |

| Honda 10W-30 |

3.50 | SL | 12 | 1 | 29 | 1697 | 1200 | 1345 | 87 |

| Mercury 10W-30 |

4.25 | SJ | 6 | 274 | 948 | 301 | 1123 | 1247 | 0 |

| Suzuki 10W-40 |

3.95 | SG | 18 | 252 | 781 | 317 | 1171 | 1299 | 5 |

| LubriMatic 10W-30 |

3.95 | N/A | 15 | 365 | 1268 | 322 | 1270 | 1320 | 1 |

| Evinrude/Johnson Four-stroke |

4.15 | N/A | 13 | 274 | 859 | 300 | 1207 | 1155 | 4 |

| Evinrude Synthetic Blend |

6.75 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 31 | 3052 | 1056 | 1188 | 3 |

| Pennzoil 10SW-30 |

1.29 | SL | 9 | 234 | 18 | 2000 | 1286 | 1345 | 216 |

| Valvoline 10W-30 |

1.29 | SL | 8 | 29 | 21 | 2239 | 1226 | 1335 | 0 |

| Wal-Mart 10W-30 |

1.19 | SL | 7 | 0 | 14 | 2017 | 1118 | 1245 | 1 |

| Castrol GTX 10W-30 |

1.66 | SL | 13 | 1 | 14 | 1748 | 1204 | 1335 | 84 |

| Mobil 1 10W-30 |

4.95 | SJ | 8 | 186 | 601 | 1352 | 1256 | 1343 | 0 |

Get The Rust Out

Four-stroke outboards are more prone to corrosion than their two-stroke cousins. Whereas a two-stroke always has a film of oil on its cast-iron cylinder walls, a four-stroke's bottom piston ring scrapes away the protective oil. Counting the steel valves, seats, cams and springs, it has more parts susceptible to rust and corrosion. Mounted on the stern, its open exhaust valves are only inches from the water, allowing moisture and humidity to condense onto the unprotected cylinders and steel components.

Being our usual inquisitive selves, we wanted to find out if the claims were true. Do marinerated oils provide better corrosion protection than automotive oils? Unfortunately, we were not able to test the rust resistance of every brand, so we picked the three major outboard lubes, an aftermarket marine oil, two popular automotive samples, and the Mobil 1 synthetic. We cut steel flat stock into pieces, scuffed them clean with a nonmetallic abrasive pad, and degreased them with acetone. After soaking each piece in its respective test oil for a minimum of 12 hours, we heated them to 250 degrees several times to duplicate the oil temperature present in an outboard. Suspended by plastic tie-wraps to avoid dissimilar metal interactions, the samples spent 30 days exposed to Florida salt air, protected from sun and rain, and then several months in an unheated garage. This corresponds to an engine that was used for a short while and then stored until another season.

We asked for comments on our "unscientific" corrosion test from George L'Heureux in the Specialties Development section of Infineum USA, one of the world's largest oil additive companies. "Your home-brew test is not unlike some of the rust tests we run in the industry," L'Heureux told Bass & Walleye Boats, "though specialized testing takes place in salt-fog cabinets rather than outside."

The results were eye opening. For years, one of the myths about synthetic oils was that they "ran" off internal parts when the engine stopped, and did not protect them from rust. The Mobil 1's performance debunked that theory, as did Evinrude's Synthetic Blend. Pennzoil showed good corrosion protection. Ditto with Mercury and Sierra. Castrol GTX provided fair protection, but the "made-for-outboards" Yamaha oil did not fare as well as the others.

Our corrosion study netted surprising results. Before torture testing, each steel sample was soaked in the indicated lubricant (listed from top): Yamaha, Castrol GTX, Sierra, Mercury, Pennzoil, Mobil 1 and Evinrude Synthetic Blend.

Builders' Recommendations

Most outboard companies recommend that the oil and filter be changed after every 100 hours of use, or once a season, whichever comes first. A few specify a 100-hour or 6-month change interval. Be sure to follow your owner's manual for the correct oil grade, rating, and maintenance intervals. Outboard companies recommend a 10W-30 and/or a 10W-40 oil for their products. In warmer climates, Mercury suggests the use of its sterndrive 25W-40 oil, and Suzuki advises a 20W-50 grade.

When asked specifically about the use of nonfactory oils and synthetic oils in their outboards, each company had a different take. Yamaha said synthetic oils were not recommended because they had not been tested on the company's outboards. Mercury was quick to repeat the owner's manual recommendation, even when asked about synthetics. Bombardier (Johnson and Evinrude) says its premium synthetic blend is the best choice, and that its use doubles the oil-change interval (200 hours). It also advised owners to follow their engines' manuals. Honda said to use any oil that meets its requirements. Suzuki did not recommend synthetic oil, saying its outboards are designed and tested for petroleum-based products. Mobil Oil, on the other hand, told us that its Mobil 1 would work well in all four-stroke outboards.

Ultimately, consumers will have to determine how the use of a nonrecommended oil affects their engines' warranties.

Our Conclusions

Which four-stroke oil wears the crown? As we discovered, high price doesn't necessarily mean better performance.

Here's what we learned from our testing. Although there's not a large variation between automotive oils and specialty lubes in terms of percentages of anti-wear additives, there are differences in their detergent/dispersant formulas. We also discovered that high prices do not necessarily mean better oils, at least according to our rust test and spectrometer analysis. Due to the complexities of lubricating outboards in a harsh environment, each oil has its strong and weak points—and each should work adequately in a four-stroke outboard, as each meets outboard manufacturers' requirements. The low-priced Pennzoil 10W-30 is outstanding in rust prevention and is formulated with a stout anti-wear package of zinc, phosphorous and molybdenum. It also has a good percentage of detergent/dispersants. Pennzoil is our top pick based on the information we gathered. We believe that Mobil 1 is a good choice in synthetic automotive oils, but the much pricier Evinrude Synthetic Blend isn't a bad value if you're able to get 200 hours between oil changes in your Johnson or Evinrude four-stroke.

When the FC-W certified oils appear later in 2004, we may do another comparison to see if the certification improved the present crop of lubes. Regardless of whether you feel comfortable using automotive oil or insist on a marine-rated product, the most important consideration in terms of engine longevity is to change oil more frequently than the maximum recommended interval. In the long run, oil is cheap, but repairs are expensive.